Chinese models are DOMINATING the open-weight LLM space.

Open-weight models are freely available to download, run, and fine-tune, often released with highly permissive licenses. Some open-weight models are also open-source, meaning the code and training data to reproduce those models are openly available as well.

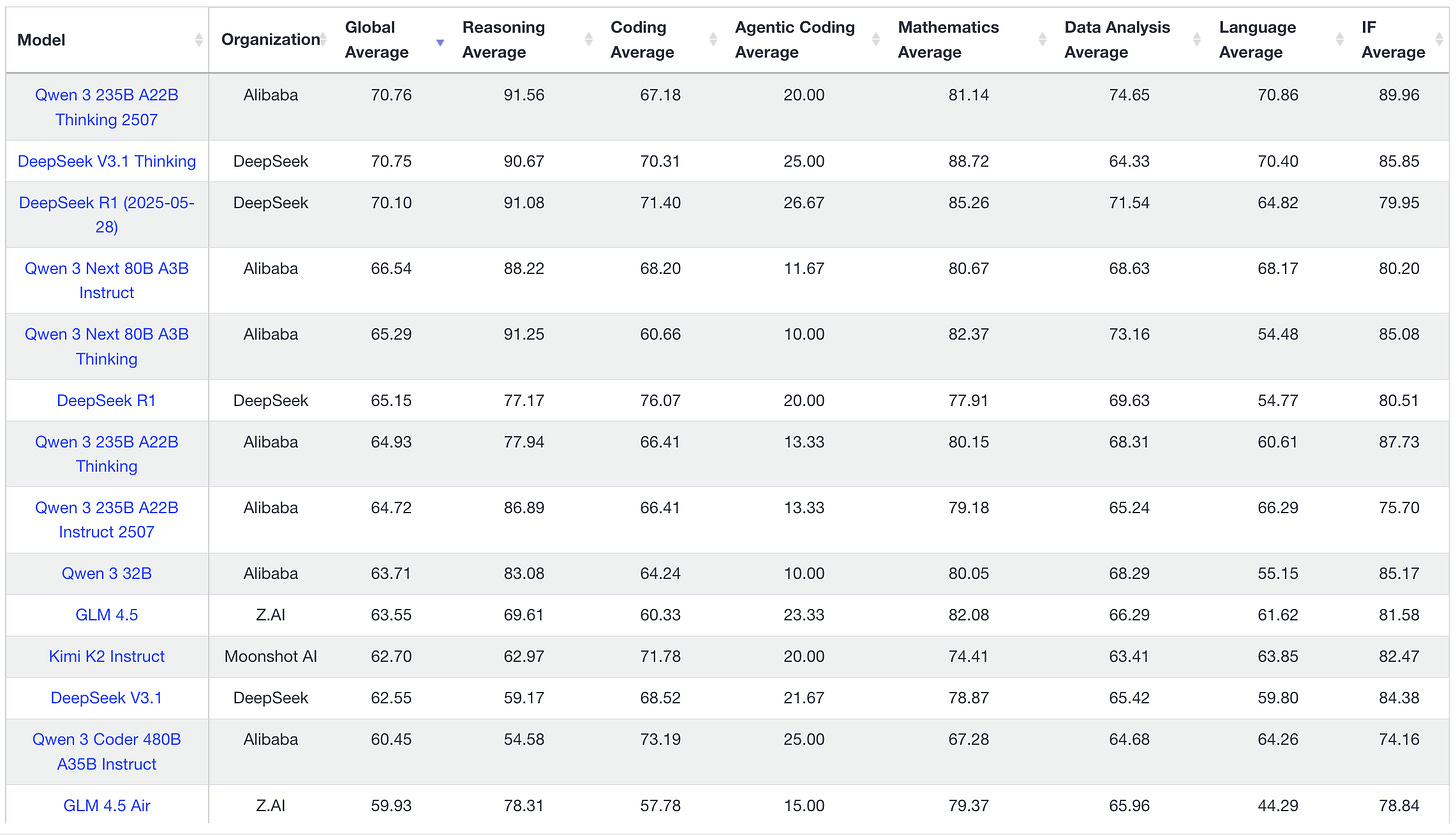

These models are incredible, and compete with or even outperform leading proprietary US models on common benchmarks while costing a small fraction of the price.

One might be surprised to learn that not only are Chinese tech companies making AI models freely available, but the Chinese government has also promoted open models as part of its AI strategy. In July, China released its Global AI Governance Action Plan, heavy on “international public good,” “collaboration,” and “openness,” which sounds lovely until you remember that China maintains one of the most restrictive and censorious regions of the internet.

So what gives? Why is the Chinese government suddenly a champion of openness in AI?

Some of the stated aims are straightforward. Open-weight models can streamline domestic adoption of AI tech by increasing collaboration between Chinese corporations, government, and academia. Open-weight models also speed up iteration, and allow researchers or military stakeholders to fine-tune high-quality models to build capabilities that would otherwise be out of reach.

Those less familiar might be concerned about data privacy and security when using Chinese models. However, using these models does not require interacting with or sending any data to Chinese servers whatsoever. Top open-weight models are hosted by a multitude of US-based providers (like DeepInfra and Cerebras) who process queries in US-based data centers. Chinese companies have no visibility into, and generate no revenue from, this usage of their models.

One prominent hypothesis is that if global developers adopt Chinese AI models, China could set standards that steer AI development worldwide. I’m skeptical. In the past, choosing open alternatives like Android over iOS or Linux over Windows meant rewriting nearly everything from scratch. But LLMs are different: they process and generate natural language, making them perhaps the most natively interoperable technology ever invented. With tools like OpenRouter, swapping models is often as simple as changing a single parameter in your code. The same prompt can be processed by different LLMs. Lock-in doesn’t exist here.

I’m no expert on China. I’ve never even been to China. And even for experts of China, it can be really difficult to decipher the priorities of the CCP. It’s plausible that the CCP’s embrace of open-weight models is purely to promote domestic AI adoption, or simply an emergent phenomena, or even a defensive response to chip bans implemented by the US to slow China’s AI progress.

Nevertheless, I can’t help but notice how flooding the market with free open-weight LLMs seems to rhyme with how China rose to dominance in manufacturing.

Innovation in the US is fueled by investors, based on the perceived potential for profit. Innovation in China is largely steered top-down by government priorities. The CCP often prioritizes national capabilities over profits.

This is apparent in China's manufacturing playbook. Over the last few decades, China has provided massive government subsidies to manufacturers, producing and selling low-cost products worldwide, often at a loss. These massive subsidies allowed China to dominate key industries, including producing 80% of the solar energy supply chain and over 70% of electric vehicles worldwide. Prioritizing national capacity over profit has transformed China into the world's sole manufacturing superpower with over 30% of global manufacturing output, exceeding the nine next largest manufacturers combined.

China’s subsidized manufacturing, unleashed on global markets, devastated US manufacturing capacity, including in sectors critical to defense. China now acquires high-end weapons systems five to six times faster than the US and has over 230 times our shipbuilding capacity. They have created a massive military advantage by reinforcing China’s wartime production capabilities and undercutting those of the US.

Similarly, open-weight models reduce AI labs' pricing power and consequently make massive R&D investments harder to justify. OpenAI spent years and billions to produce GPT-5 only to receive fairly mixed reviews, including disappointment from some users and revolt from others (personally I think it's a pretty great model—but not an equivalent leap forward to GPT-3 and GPT-4). Meta spent billions on AI infrastructure and training, but Llama 4 launched to a lukewarm reception and failed to outperform cheaper and smaller open-weight Chinese models. Why spend billions training a model when a superior Chinese alternative might appear tomorrow—released for free and hosted at rock-bottom prices by competing US providers?

Open-weight AI models are great for users of AI, including startups, brands, and even the sellers of AI inference—just like cheaper manufacturing is good for consumers and sellers of cheap products. AI startups like mine benefit from being able to train on top of these incredible open-weight models. But–whether intentional or not–cheaper AI inference makes it harder for US companies developing foundational AI, just like cheap subsidized manufacturing undercut US factories.

Outsourcing created short term savings but left long-term dependencies. When the US sent production abroad, we didn’t just lose factories–we stopped reinforcing the skills, knowledge, and supplier networks required to produce. Basic capabilities like machine-tool and tool-and-die capacity halved. Even if reshoring makes economic sense, the industrial commons no longer exists to support it. Freely available open-weight models could have a similar, if smaller, impact in AI by pushing more engineers to specialize in fine-tuning models and fewer to build models from the ground up.

Silicon Valley is concerned. Sam Altman is openly worried about China, and open-weight models in particular. In a recent Washington Post op-ed, Altman warned that "a democratic vision for artificial intelligence must prevail over an authoritarian one," citing Putin's prediction that whoever leads in AI will "become the ruler of the world," and China's ambitions to become the global AI leader by 2030. Dario Amodei of Anthropic has called export controls on chips existentially important to slow down Chinese progress in AI. Marc Andreessen declared DeepSeek AI's Sputnik moment.

Washington has also noticed the threat, and has encouraged American AI companies to release their own “leading open models founded on American values.” OpenAI recently did just that with the release of open-weight gpt-oss, admitting that they were motivated to do so by Chinese open-weight models.

But this response might play right into China's hands. A race to the bottom benefits Chinese labs because they’re less dependent on potential profitability and ROI to solicit funding.

Could it work?

On one hand, almost certainly not—China won’t be able to derail our AI with nearly the same efficacy as it did manufacturing. Too many powerful interests, both public and private, are aware of the stakes in this race. And too many tech giants in the AI race have deep enough pockets and massive unrelated revenue streams to fund continued progress, even on thin (or negative) AI margins. US labs still appear to have a meaningful lead in frontier AI.

On the other hand… It's already having some impact. Without China’s open-weight models, inference prices from frontier labs in the US would likely be higher than they are today. Businesses and consumers would have less exposure to Chinese models if it meant sending data to Chinese servers, so new models shipped in the US would appear more impressive. The market for AI would be less competitive, but ROI for labs in the US would be higher. Whispers of an AI “bubble” might not be so loud.

China's low-cost manufacturing gave it the capacity to outproduce the US in everything from consumer goods to military hardware and created dependencies that could prove fatal in conflict. Flooding the market with free high-quality AI models might do the same, even if to a lesser extent: build China's AI capabilities while making it harder for the US to sustain ours.

It worked once. Why not try it again?