What Can’t Be Automated?

The Last Human Bottleneck

Many of the people pouring hundreds of billions into AI seem confident it won’t eliminate jobs.

David Sacks, White House AI Czar: “Apocalyptic predictions of job loss are as overhyped as AGI itself.”

Jensen Huang, Nvidia CEO: “AI has no possibility of doing what we do… in no job can they do all of it.”

Marc Andreessen, a16z: “The employment shifts everybody’s worried about are actually not going to happen at anywhere near the velocity people think.”

Markets automate whatever they can, as cheaply as they can. Human labor fills in the parts that can’t be automated—the bottleneck. So the question is: what’s the bottleneck that will keep humans in the loop?

If there is one, we should be able to say what it is. I haven’t heard anyone do so.

Historically, as more of a process gets automated, the remaining human work becomes more valuable, not less. Automate 99% of a factory and the one remaining human unlocks all the value the other 99% creates. That person becomes incredibly valuable—not despite the automation, but because of it. Wages go up. Jobs might increase.

Until that bottleneck gets automated too.

This has happened many times before.

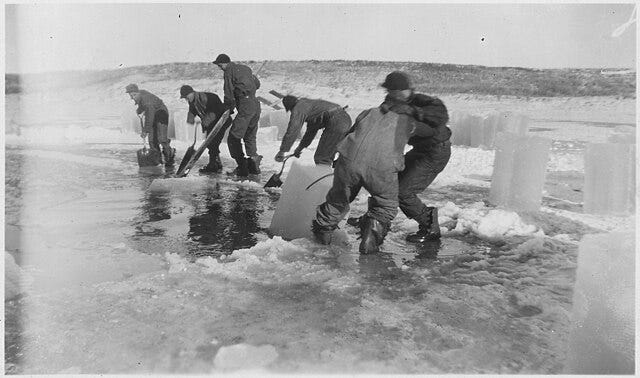

Ice harvesting. At its peak in the 1880s, the US ice trade employed 90,000 workers and 25,000 horses, harvesting 25 million tons annually to meet exploding demand from railroads, meatpackers, breweries and growing cities. Armies of human ice cutters manually sawed giant blocks of ice where it formed naturally from lakes, ponds, and rivers. Then mechanical refrigeration became available, and by 1914, manufactured ice matched natural production. By 1950, the entire industry was gone.

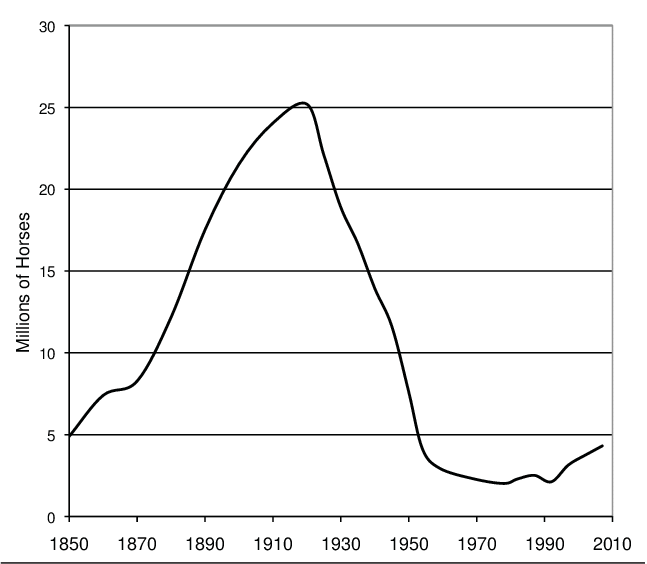

Horses. In 1860, the US had about 1 horse (or mule) for every 5 people. By 1910, it was 1 horse for every 3—horse population outpacing human population growth. Steam and rail didn’t kill the horse, but actually made horses more valuable as the last-mile bridge between rail depots and doorsteps. Then the automobile arrived, and the horse population plummeted from 25 million in 1920 to 3 million by 1960–an 88% decline in 40 years.

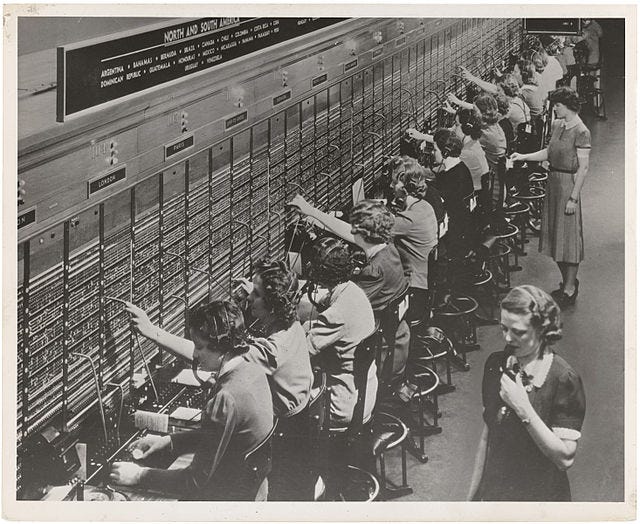

Switchboard operators. In the late 1940s, AT&T was one of the largest private employers in the country with over 350,000 switchboard operators. About 1 in 13 working women was a switchboard operator. Call volume was exploding, and humans were needed to route every call, so the number of operators nearly doubled from the 1920s to the 1940s. By the 80s, 90% of those jobs had disappeared.

In each case, as the industry became more automated, demand for humans to fill the remaining bottleneck grew—but so did the incentive to automate it.

Once you’ve automated everything else, the remaining bottleneck is a contained problem with a proven market. There’s already massive demand for ice. People already have and use telephones. Infrastructure is built, revenue is flowing, and the shape of the problem is clear. The golden age of the bottleneck creates maximum incentive to eliminate it.

So it’s not surprising that we haven’t seen major job loss yet. David Sacks points to “job creation”. Marc Andreessen describes “an AI hiring boom” where companies are “hiring the experts to actually craft the answers to be able to train the AI.” A Yale/Brookings study finds “no discernible disruption” to employment. But a surge in demand for humans to train their own replacements isn’t evidence that the jobs are safe. It’s evidence that the path to automating the bottleneck has never been more direct.

Previous revolutions had obvious limitations. The Industrial Revolution automated narrow, repetitive physical labor. Computers automated calculation. In both cases the boundary was obvious — humans were needed for everything requiring flexibility, judgment, creativity, or common sense. AI lacks any similarly obvious boundary.

Another common refrain is that “there’s no evidence of AI eliminating jobs.” This could have been said about every previous revolution — right up until the collapse. Of course there’s no evidence. It hasn’t happened yet. But there’s plenty of evidence that markets automate everything they can and will continue to do so.

I understand why people in positions of influence feel the need to be reassuring. People are scared. And there are genuinely scary risks when it comes to AI. But living in a world of such abundance that most human labor is no longer necessary? That is not one of them. Telling people their jobs are safe isn’t just unconvincing — it’s a failure to articulate a positive vision of a future where AI goes right.

Until now, we needed a lot of people to have the same skills. It made sense to send everyone to school to learn the same things, graduate with the same majors, sit in classrooms driven by what society needed rather than what anyone found exciting. People take monotonous jobs because for most people, that pays better than pursuing your deepest and most unique curiosities and passions. AI could make that trade-off obsolete.

We’re appropriately skeptical of “shared prosperity” — historically, it’s meant central planning, forced labor, and authoritarian control. But an abundance economy doesn’t require any of that. We already tax a huge share of economic activity. In an abundance economy, we can fund a baseline where everyone genuinely thrives—on lower taxes, and without central planning or coercion. Nobody is forced to do or not do anything, because production doesn’t depend on anyone’s labor.

And in that world, the most valuable thing a human can do might be the most human thing a human can do.

AI will be able to automate and scale anything we know we want more of. But the things that captivate us — a song, a product, an experience, an idea — do so because they surprise and challenge us. Not just any surprise — novelty is cheap, and AI can explore the search space of novelty faster and more efficiently than we ever could. What’s rare is novelty that resonates — something genuinely new that also feels right. And, at least until AI can simulate us perfectly, the only way to know if something out-of-distribution resonates with a human is to be one.

An AI-driven economy will continuously hunger for that data — authentic reactions from people with real subjective experiences, real tastes, real obsessions. Every human has a unique point of view. We don’t foster that today because it’s not economically useful. Most people spend their careers doing repetitive, mind-numbing work because that pays better than pursuing what actually fascinates them.

In a world where anything that can be taught can be automated, the most economically productive use of a human might be leaning into exactly the things that make them most human. For the first time, the economy might reward us for being ourselves.

Good riddance to bottlenecks. Let automation expand what humans can be—not force us into what can’t be automated.

Love this line:

“And, at least until AI can simulate us perfectly, the only way to know if something out-of-distribution resonates with a human is to be one.”